9-3-2020

New Missouri Statute Encourages Public-Private Partnerships for Broadband Infrastructure

For many years Missouri cities and counties have used Community Improvement Districts (CID) and Neighborhood Improvement Districts (NID) to finance public infrastructure and to encourage economic development in designated geographic areas (“districts”) located within their borders. CIDs and NIDs are well-suited for this purpose, because when approved by property owners or individuals living in the district, a CID or NID can raise revenues through taxes and/or special assessments on property located or sales occurring in the district. For more general information about CIDs and NIDs see Missouri Local Incentives.

Up until now Missouri statutes did not specifically state whether internet broadband was a “public improvement” eligible for financing by a CID or a NID. However, in this past session the Missouri legislature enacted HB 1768 which made some significant changes to both the CID and the NID Act. In each case a new provision has been added that permits these districts to be used for public-private-partnerships that will construct or improve broadband infrastructure. CIDs and cities and counties that create NIDs are now specifically authorized:

“[T]o partner with a telecommunications company or broadband service provider in order to construct or improve telecommunications facilities which shall be wholly owned and operated by the telecommunications company or broadband service provider…”

However, this specific authorization is limited to areas that are certified by the Missouri Department of Economic Development to be unserved or underserved. As a practical matter this means that the area to be covered in an agreement with a telecom or other broadband service provider (an “ISP”) must currently have internet service below speeds of 25 mps download and 3 mps upload. This requirement is imposed by cross-reference to the Missouri’s Broadband Grant Program statute.

How can Missouri cities and counties use a CID or a NID to “partner” with a broadband provider and bring broadband service to their community?

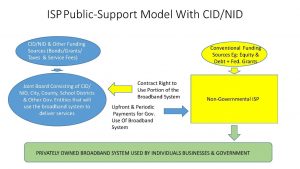

One example might be for a CID (or the City/County acting through an NID) to contract with an interested ISP to build broadband assets and to deliver broadband service to residents and businesses located in the district, in exchange for an upfront lump sum cash payment. This cash payments would constitute the CID/NID’s “contribution” to the partnership formed with the ISP. The ISP partner would obtain conventional financing and/or grants from the federal government to pay for the balance of the cost of the system, and the ISP would operate and maintain the newly-constructed system. Residents and businesses would subscribe for service on the system pursuant to a normal internet service model, but the cost of that service could be more affordable, because a portion of the capital investment was covered by the CID and/or NID.

To further government and public purposes, the newly-constructed broadband system could be made available for use by the city and county government and other government entities such as the local school district, the county public health department and municipal utilities. These “government users” would use broadband to better deliver government services to the district’s residents and businesses. For example public schools might use the system to provide remote learning opportunities to children – and help solve the homework gap.

The upfront investment from in the partnership by the CID/NID could be financed with debt paid by revenues produced from special assessments, taxes imposed in the district, or from fees paid by local government users of the system.

The picture below illustrates how this “ISP Public Support Subsidy Model” would work. The CID or NID provides a portion of the funding for the broadband project, along with possible ongoing contributions by other local government entities that will use and benefit from the system. Together, these public entities “partner” with an interested ISP to make broadband and its applications a reality for the district’s residents and businesses.

In the above-example, the CID or NID is only one part – albeit a critical part – of an overall plan to bring public support to a broadband infrastructure project that will be owned and operated by a private ISP. Implementing the plan assumes that residents and businesses located within the CID or NID boundaries want broadband – and that they are willing to join together to help fund the “gap” that currently makes the expansion of broadband into their community financially impossible for the ISP acting alone. However, one advantage of taxing districts is that their boundaries can be tailored to include those areas where residents and property owners clearly favor the approach and are willing to join together to help pay for it.

This and other approaches are described at pages 48-54 of the Workshop Report prepared for Bollinger County, Missouri, as part Broadband Workshop hosted by University of Missouri System earlier this summer.

Whether a CID or an NID is a practical solution for a particular community requires individualized legal and financial advice of professionals. Many steps are necessary to properly explore and implement a workable financing plan that adequately protects the interests of the public and that provides a fair economic return on the ISP’s investment. That said, the changes made by HB 1768 are a welcome new tool to allow local communities to begin to enjoy the benefits of Broadband.